The German Covid Mystery

- Henry & Henry

- Nov 19, 2020

- 6 min read

In the course of the last 7 weeks since we arrived in Berlin, our new home city, we have been presented with a unique and compelling insight into the commonalities and the differences between two major European countries, specifically the UK and Germany. Anyone who has visited Germany at some point in their life will have an inkling of some of the obvious cultural differences, and we are reminded of these on a daily basis as we become accustomed to our new life here.

At present, we are going through a period of adjustment and as with any change, we are finding some of the practices and customs at times frustrating and at times heartwarming. The comparison is even more pertinent at the moment as both countries strive to combat and survive the Coronavirus pandemic. How different it feels here in Berlin from what we encountered in York earlier in the year when the first lockdown was introduced. We don’t know what it felt like in Berlin at that time, since we weren’t here to experience it, but if the present is any guide, it feels very different. Apart from the fact that the restaurants, cafés, bars and hotels are closed for business here, most other walks of life feel fairly normal and the roads are full of traffic, the trains, trams and buses are well-used, and the commercial centres are not eerily silent and full of tumbleweed. Yet there is a sense of concern in Germany and in Berlin at the rise in coronavirus cases and a continued call for responsible behaviour in order to safeguard the vulnerable and elderly and to prevent the intensive care wards from becoming overloaded.

However, we don’t wish to revisit the debate of how we should tackle the crisis in this blog post, instead we wish to highlight some of the observations we have made. One glaring difference between the two countries is the much lower number of coronavirus cases and the number of deaths in Germany, something that is fairly well documented in the media. Why is this? What are the factors at play? We can only speculate, but we have our own ideas, and it very much links to the daily habits and lifestyle practices that Germans have adopted. We will suggest some of the possible reasons here.

How often do we associate the German diet with eating meat, lots of it, especially pork? This is a well-worn cliché and while it is still evident, meat consumption is reported to be declining. According to a recent study, the number of vegans in Germany has doubled in the last four years and 30% of Germans surveyed in the study now describe themselves as flexitarians. Whilst this trend is also evident in the UK (which was unfortunately not included in the comparison), it’s interesting to note this sea change in Germany. What is also evident, based on personal observation, are the foods that Germans appear to be buying on a regular basis. Fruit and vegetables feature highly in their baskets and trolleys, hardly surprising when there is such an abundance to choose from. Processed foods and convenience foods still play a part, as is surely the case everywhere these days, but apparently less so than in the UK. Perhaps this is connected with the importance of making time to sit down and eat meals together with other family members at a dining table.

Ritual still appears to play a part here in Berlin. On Sundays, other than bakeries and florists, all the shops are closed and it’s customary for people to visit family, go for walks in the park, cycle or jog. We share the Germans’ passion for parks and trees and we have spent many an hour recently walking down tree-lined streets and breathing in the fresh air and earthy aroma of Autumn leaves. In fact, both of us feel we have never seen so many trees in a city. Trees, we now know, provide an important life-support system for cities. They help to filter out air pollution and this is particularly welcome in a city the size of Berlin, where car use is still high despite the excellent public transport network. Air pollution has been proven to increase the risk of death from corona infections and according to a recent alarming report from Mainz University Hospital, it is estimated that 15% of all Covid-19 deaths are due to ‘fine dust’, or what we term as particulates. How vital then that we try to offset this risk by planting trees close to our roadways. This is sadly much less prevalent in the UK and perhaps this is a factor that needs to be given consideration when we are confronted with the high rate of coronavirus-related deaths in the UK.

Fresh air is valued highly in Germany, and something fresh air-related that the Guardian newspaper picked up on a couple of months ago may also have a bearing on the Corona figures in Germany, namely, ventilation. Described as a “national obsession” it explains that it’s standard practice for Germans to ventilate the buildings they inhabit or work in by periodically flinging the windows open long enough to allow for a full exchange of air, and it’s thought that this may play a role in reducing the infection rate of the respiratory virus that we’ve come to know as Covid-19. So convinced are the German authorities of its current relevance, that they’re bringing machines into some school classrooms that literally clean the air. Perhaps not surprisingly, this is in addition to fresh air ventilation. Is this simple and long held practice a clue to why Corona figures in Germany are lower than in many other European countries?

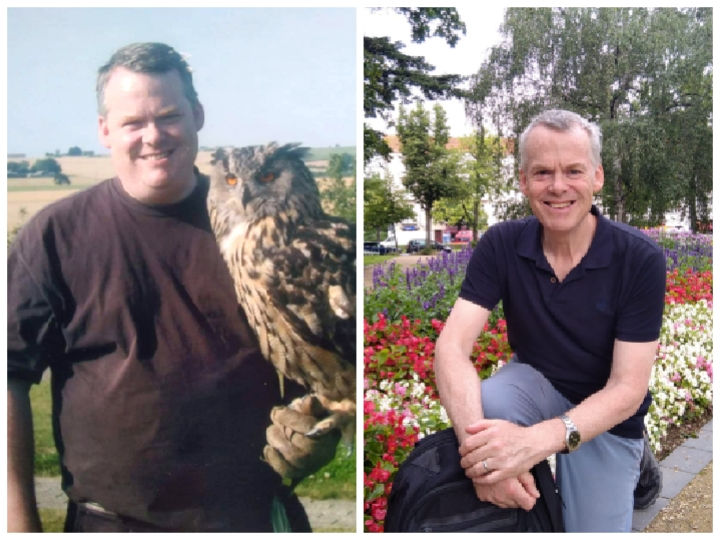

Perhaps not surprisingly where health is concerned, the two of us feel compelled to frequently revisit the role of food and eating habits. Something in Berlin has taken us by surprise, and of course we cannot comment on the whole of Germany in this regard, but there is undeniably less of something here than we might have been expecting and that is obvious obesity. There is an abundance of lean people such that for the first time in a couple of decades, spent in two areas of northern England, I (Annette) don’t feel that I look “thin” anymore. It may help that I’m also building muscle thanks to walking up multiple flights of stairs and opening German doors (how do they make the doors so heavy?!) But seriously, this is a bit of a revelation. We’ve never formed the impression that the German diet classifies as “light” so what’s happening? Do they eat smaller portion sizes? Is it the exercise and fresh air? (probably not; you can’t out-run / walk / cycle a bad diet, certainly not without a lot of effort). What about what people here do eat? We’ve already made reference to fruits and vegetables here, but these are not the only sources of something really key: fibre. A glance at the bread counter of any supermarket confirms that Germany still has a passion for bread, specifically wholegrain bread. Could it be that refined products don’t have quite the hold here that we typically see in Britain? And why might it be so useful just now? Well, we know that amongst its many benefits, fibre escorts excess cholesterol out of the body which is a means of lowering the incidence of cardiovascular disease, and CVD is one of the “underlying causes” frequently referred to in connection with Covid-19 outcomes. But could there be something even more directly relevant? It appears there might. It will come as no surprise to anyone fascinated by the new field of research into the human microbiome that gut bacteria, and their food - fibre, play a huge role in multiple aspects of our health including immunity and this has already formed part of a study considering this very topic in the context of this pandemic. We hope there will be more such studies to come so that we can better understand it.

We will continue to look for clues to respond to our curiosity about Corona virus outcomes in Germany and we hope that the potential list of positive effects that we’ve outlined here, and which may play a role in explaining the German experience will be expanded upon across all Western societies as a means of mitigating and preventing any similar events. Perhaps we’re finally learning that we need to live differently?

)_20230830_134131_0000.png)

Comments