Mediterranean or Vegan?

- Henry & Henry

- Feb 16, 2021

- 6 min read

The Journal of the American College of Nutrition recently published the results of a fascinating study comparing the effects of eating a traditional Mediterranean Diet and a Low-Fat Vegan Diet on body weight and cardio metabolic risk factors. Whilst there is a good deal of evidence to support both diets in terms of their ability to improve these risk factors, the study aimed to ascertain which of the diets was most effective in doing so. The results were interesting and have inevitably provoked a good deal of discussion amongst health professionals and those interested in the field of nutrition, not least because of the huge toll that excess body weight and cardiovascular disease takes on the health of humans worldwide.

Before considering the results of the study and what conclusions may be drawn, let us first take a look at the design of the study. The study was a randomized crossover trial in which 62 overweight adults were randomly assigned to a Mediterranean or vegan diet for a 16-week period. The participants then reverted to their baseline diets for 4 weeks, after which they began the opposite diet for 16 weeks.

What did both diets actually consist of?

The Mediterranean diet participants were asked to consume a specified amount of vegetables, fresh fruits, legumes, fish or shellfish, nuts or seeds, and white meats and they were also asked to use 50g extra virgin olive oil per day. The low-fat vegan diet consisted of vegetables, grains, legumes, and fruits with the aim of obtaining 75% of energy from carbohydrates, 15% from protein, and 10% from fat. Participants could eat as much as they wanted provided they stuck to these guidelines.

At the end of the study, the actual fat intake was calculated at 43% of calories in the Mediterranean group and 17% in the vegan group. The vegan group also consumed around 500 fewer calories per day than the Mediterranean Group, had a higher intake of fibre and lower intakes of saturated fat and cholesterol.

What were the results and what conclusions can we draw?

For those interested in a detailed analysis of the results of the trial, we suggest reading the full study here. The headline results show that a low-fat plant-based diet reduced body weight, fat mass, and visceral fat, increased insulin sensitivity, and reduced levels of total and LDL cholesterol, compared with a Mediterranean diet. Interestingly, systolic and diastolic blood pressure decreased more on the Mediterranean diet, though reductions were seen in both groups.

What does this study tell us? Does it present a compelling argument for following a low-fat wholefood vegan diet first and foremost? Can we position this diet as the gold standard of diets looking at it from the perspective of maintaining and improving cardiovascular and metabolic health? Certainly, there are solid research-backed studies that show the benefits of following a low-fat plant-based diet for heart health and diabetes as evidenced in a number of fascinating landmark studies which are listed below:

Neal D Barnard et al: A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes

Caldwell B Esselstyn Jr et al: A way to reverse CAD?

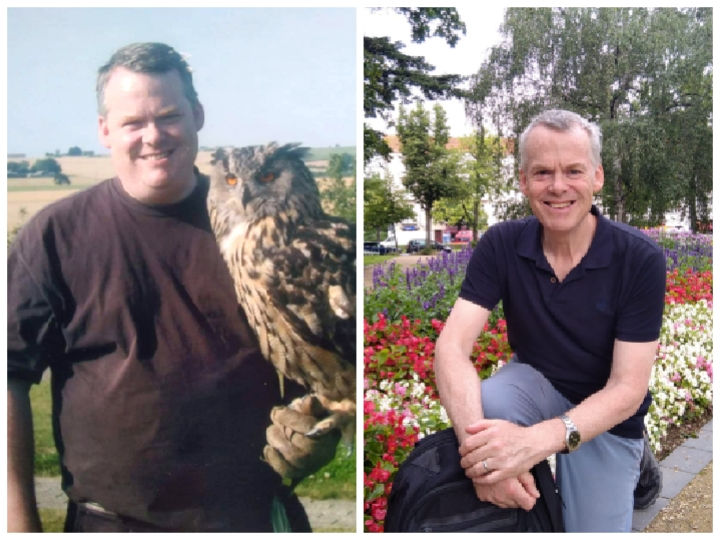

In all of these studies, the dietary approaches adopted were intended as therapeutic interventions to improve or reverse a disease or condition. It’s probably fair to say that for many people, it may seem beyond the scope of what is possible to consider restricting fat intake to 10% of overall daily calorie intake. Is this even necessary or indeed essential? We think not, in terms of everyday living, unless one is wanting to improve or reverse a chronic condition. What we do believe nonetheless is that the standard Western diet veers too far in the opposite direction, and that consumption of fat is far too high and in excess of what it should be in order to maintain good health in the longer term. We, Annette and Graham, consume on average somewhere between 15%-20% of our daily calories as fat, and the majority of that fat is in the form of unsaturated fat, with saturated fat kept to a minimum (this is not a problem on a wholefood plant-based diet so long as you are not eating ‘solid at room temperature’ fats like coconut oil). In fact, it may come as a surprise to learn that we do not include any oils in our diet (ie. olive oil, rapeseed oil, sunflower oil etc). Why is this? The simple answer is that oils are 100% fat. We prefer to obtain our fat from the wholefood that it comes with, so for example we eat whole olives, chia seeds, flaxseed, hemp seeds, walnuts, almonds, brazil nuts and cashews. Fat is also present in every single plant food we eat, since no wholefood comes without all three macronutrients as well as fibre. The percentage of fat consumed in the Mediterranean diet in the study we have described here appears high to us at 43%. The average human body does not require this much fat and we know that high consumption of fat can ultimately lead to insulin resistance and further complications. Is it possible that this is the reason why the bio-markers for cardiovascular disease associated with this study’s diet are unchanged except for blood pressure? Would this diet over an extended time lead to less than desirable consequences? This is open to debate, but a small tweak downwards in the percentage of fat consumption could just make the difference.

At the risk of stating and restating the obvious conclusions from this study, a diet that is largely based on whole plant foods, with an emphasis on fruits and vegetables leads to the sort of health outcomes that most of us are keen to see in our own lives.

The logical next conclusion, then is surely to merge the best of each diet into one? Since the vegan diet here was only surpassed by the Mediterranean diet on one of the measured outcomes, is there anything within a low fat vegan diet such as this one that could be done differently to achieve even better blood pressure results than were observed in the study? If the hypothesis of the authors of the study is correct, ie that the Mediterranean diet may have had better vitamin E levels, probably from the olive oil and that this may correspond to the lower BP results, then can the same be achieved within the vegan diet? The answer is clearly yes. But does that mean that wholefood vegans should start glugging olive oil?

Olive oil is hailed in various quarters for demonstrating positive results for cardiovascular health, but should we perhaps bear in mind that the inclusion of olive oil is often set against what test subjects and patients used to consume on their standard western diet? Someone switching from a diet high in saturated animal fat to a diet where the main source of fat is the mono-unsaturated olive oil, may well find their health has improved. But olive oil is still pure fat, as stated above, with its 9 calories per gram and complete absence of fibre. The olives themselves have more to offer, as do all nuts and seeds compared with their isolated oils. Perhaps we can give you an example. We often use nuts, and especially seeds, for making salad dressings. Our top go-to seeds are those that are rich in Omega 3 fatty acids, flax, chia, hemp seeds (there are some examples of how we use seeds in dressings in the recipes section of the Conversation page of our website). Let's have a look at flax. The percentage of fat in flaxseed oil is 100% and there are 0 grams of fibre, whereas 71% of the calories in the seed are from fat and 100 grams of flaxseed, will give you around 7.7g fibre.

But what about vitamin E? Nuts and seeds are good sources of this antioxidant vitamin, with almonds being especially rich, but this suggests that fat rich foods are required to obtain good vitamin E levels, and since the parameters laid out in the study recommended just 10% of calories from fat for the vegan diet, can this fat soluble vitamin be found in other foods? The answer is yes. For the best part of a year, primarily last year, the two of us tracked our food and nutrient intake precisely for such eventualities. A quick glance at last February showed consistently good levels of vitamin E and alongside almonds and chia seeds, the other foods giving us good quantities of it included red pepper, broccoli and broccoli sprouts, kale, radicchio, kiwi, mango, butternut squash and parsnip. Legumes and grains can also contribute well to vitamin E and this includes the pseudo grains, quinoa and amaranth.

We are encouraged, if not especially surprised, to see the results of this study. Both diets, as outlined here, strongly support the efficacy of plant strong and fully plant based diets which, when based on wholefoods can be one of the best routes possible to optimum health. Who would want anything less?

)_20230830_134131_0000.png)

Comments