Breath-Induced Anxiety??

- Henry & Henry

- Apr 16, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 26, 2023

Two aspiring actors audition for the same role in a production depicting the inevitable villain, i.e. the hunter, and also the hunted. The audition is for the latter, the character being mercilessly pursued by the villain. Both auditioning actors follow the stage directions impeccably, they are at all times exactly where they should be. Actor 1, takes refuge, as directed, from the still-in-pursuit oppressor. He has fear in his eyes, he’s open-mouthed, audibly panting, his chest expanding and contracting at speed as the evil one gets closer.. Actor 2 follows all directions equally competently until he reaches the temporary hiding place. His eyes are also wide open as if in fear, but his mouth is closed. He’s not panting. His breathing is silent and it’s barely visible. Which actor gets the role? Which one has truly conveyed the stress of this part of the storyline?

You almost certainly chose the first actor for this role. He knows exactly what stress, panic and fear look like and he knows precisely how to convey it. We all know this, which is why the audience will be convinced by his interpretation. Most of us have experienced our own fear-filled and panic-stricken moments, so we know just what it feels like.

But what about anxiety? Visually it’s much less demonstrative … it may even be invisible to others. In every way, it’s less pronounced than the panic end of the spectrum and yet it may be as close as just one step away. 75% of those who experience anxiety also have dysfunctional breathing and although breathing patterns will likely not be worthy of an Oscar for their convincing portrayal, breathing will almost certainly be faster than the body requires. But this is a knock-on effect of the anxiety, surely? Yes, it certainly follows that stress, anxiety, and panic can all influence breathing and cause it to be faster. Equally though, sub-optimal breathing can exacerbate, or even cause anxiety! Why? Because if breathing is hard and fast then the message relayed to the brain is that there is a threat. The brain perceives danger even though in reality, there may not be any. The nature of this perceived state of alarm means that instructions to prepare a response are communicated back to the body, i.e. to get ready to respond to the threat, and so the cycle continues.

Why might breathing be hard and fast in the first place? In short, because it’s quite simply not unusual these days. There are multiple reasons why we might over-breathe and develop dysfunctional breathing patterns.

It may be due to a previous experience of prolonged stress where breathing speeded up and never returned to normal. In other words, it became habitual and felt normal; how we breathe day by day is our normal.

It may have been induced by illness; faster breathing often correlates with illness; after all, breathing rate is one of the ‘Vital Signs’ used to evaluate hospital patients. Again, although the illness may be long gone, the breathing habit it left may remain.

It can even relate to the food we eat. A diet high in processed foods, animal products and grains is associated with dysfunctional breathing because of the constant demand on the body to bring the pH level of the blood back to normal after eating foods that tip the balance into acidity. This may also prompt a repetitive cycle as the body learns how to switch between excess acidity and alkalinity through CO² exhalations and acid-forming foods respectively.

So, what can we do about it? Is it as simple as switching from hard, fast, upper chest, mouth breathing to soft, slow diaphragmatic and nasal breathing? In all honesty, yes. It is that simple. The challenge though is that it may not be easy. Unlearning long-held habits and relearning to breathe functionally doesn’t happen overnight. It takes commitment and a little understanding of one’s own physiology. Could some aspect of your health or your lifestyle make your job of retraining your breathing more challenging? It’s good to be aware of this to avoid leaping to the conclusion that ‘breathing doesn’t work’. Are you female? Did you know that female breathing is different than for men? This has been known since 1905 and yet to all intents and purposes, it may as well be a closely guarded secret as it’s never talked about by those who really should know. Presumably because they don’t know. Does this fact account for panic disorder being 2 - 3 times more likely in women than in men?

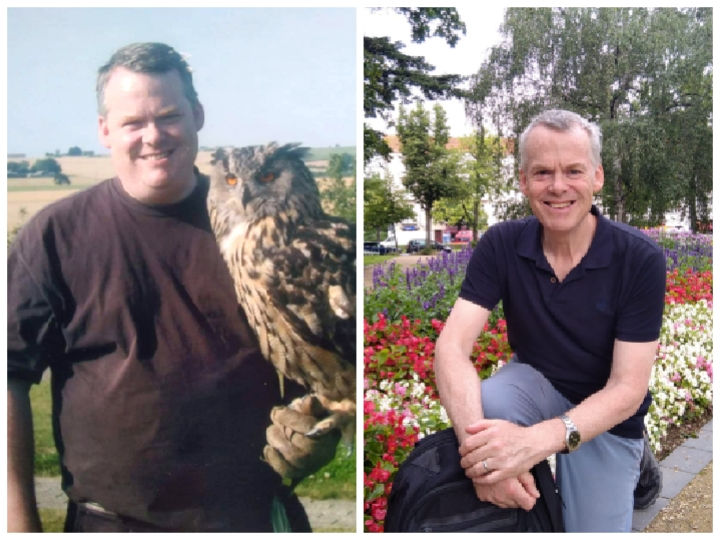

I want to leave this on an optimistic note because if sub-optimal breathing is part of the problem, then a degree of relief from anxiety is highly likely by normalising breathing patterns. And if it’s the sole cause of the anxiety well, you can draw your own happy conclusions. I have frequently stated that the worst symptom I experienced when I had Chronic Fatigue in 2018 was the anxiety which seemed out-of-control. Was I breathing too fast? I’ll never know for sure, but clearly I was unwell (faster breathing is correlated with illness), and I didn’t know what the illness meant for me long-term (a source of stress, anxiety, worry). Fast forward to now: my retrained breathing eliminated the post-covid breathlessness I was experiencing last year, it's improved my sleep, after 3 decades of insomnia and it's freed me from excessive reactivity to sometimes quite innocuous events. Do I still experience anxiety? Yes, I’m definitely still human. But do I still live with chronic anxiety? No, I do not. And that is freedom.

~Annette Henry

If you think you may benefit from some assistance with your breathing re-education, the workshop coming up soon may be relevant to you. Change Your Breathing, Calm Your Mind

)_20230830_134131_0000.png)

Comments