How We Breathe Matters

- Henry & Henry

- Apr 21, 2024

- 5 min read

This post was originally written for the beneficiaries of the Salus Fatigue Foundation. There are references to Chronic Fatigue, Fibromyalgia and Long Covid, but the breathing information and recommendations are widely applicable irrespective of health status.

Unless you have some kind of respiratory challenge, you may never think twice about your breathing, but you, and so many others, may be doing it improperly and suffering unnecessary consequences. The reference to ‘you’ is not intended to be either critical or personal. It is unusual to pay attention to this automatic moment by moment function and anyway, why would you? But it turns out breathing isn’t just the life or death matter that we often consider it to be, we must also consider the quality of our breathing, especially those of us who are unwell with a fatigue-related condition.

Why might someone with say, chronic fatigue or fibromyalgia need to give some attention to their breathing? After all, these conditions don’t tend to present us with overt breathing difficulties unlike the breathlessness of Long Covid. If you’ve heard of the ‘Vital Signs’, you’ll know that these are measures used to assess the degree of illness of hospitalised patients. Body temperature, heart rate and blood pressure are measured, and so is the respiratory rate. The faster a patient is breathing, the greater the concern. The same holds true, albeit in a less dramatic way, for those of us with any illness. A compromised state of health tends to make us breathe faster. And other aspects of disordered breathing may also be present: breathing through an open mouth during the day and / or at night, breathing shallowly, breathing hard, audibly and visibly. But if we’re getting air in, why does any of this matter?

It matters because it will worsen some symptoms and even cause others! Think about it. If it helps, picture someone who’s feeling particularly anxious, how do they breathe? They will typically breathe fast and shallowly with a lot of movement in the upper chest and they’re probably breathing through an open mouth. If they face a real and present danger then this response will be useful to help them to fight or run away. But over the long-term it can only be harmful.

By now you’re probably concluding that this doesn’t apply to you because you’re not in this state of near panic, great! But you may be doing a watered down version of it on a daily basis. Whilst you may not be about to go into panic, any level of over-breathing (breathing too much for your body’s needs) can feed into low level anxiety and stress. It can even cause those feelings. And bear in mind that what you practise during the day, however unconsciously, will almost certainly play out at night. If breathing is fast at night, your body will seek to protect you from an assumed threat by keeping you awake, or waking you up!

If you’re breathing shallowly then the air you’re taking in isn’t really reaching the lower lobes of the lungs where gas exchange takes place. This matters because it means you’re not oxygenating properly. Your muscles and organs, including your brain, depend on oxygen to enable them to function. Do you ever experience brain fog?

And if your nose is underused then cold, dry unfiltered air is being taken straight into your lungs. Not only is the air unfiltered, it doesn’t pick up any nasal nitric oxide which is the body’s first line of defence as it has antiviral and antibacterial properties. Mouth breathing can also lead to snoring and sleep apnoea.

Any or all of this combined can keep you in low level stress (and not surprisingly, any additional stress can then tip us over the edge!), disturb sleep, both in terms of quality and quantity (how often do we hear about the need for good sleep?!) and maintain our body tissues in a state of poor oxygenation (do our brains need the additional sluggishness that sub-optimal breathing brings?)

Is it all bad news? It most certainly is NOT! It’s unfortunate that, as with nutrition, breathing is not a significant part of medical training. Instead, as the only consistent medical reference to breathing is as a measure of illness, why would the rest of us conclude that there’s so much more to know and put into practice? Information about the importance of how we breathe may be lacking in medical training, but it isn’t absent from scientific research. There’s plenty we can do to retrain our everyday breathing. So where do we start?

If you still have the image of the person who is just one step away from panic, their hard, fast, upper chest breathing with an open mouth gives us plenty of scope for choosing a starting point by virtue of seeking to do the opposite. Where you start may be different from where someone else needs to start but a good rule of thumb will be to train the following:

Close your mouth for breathing. If you have the energy to go for a walk, practise nasal breathing while you walk. If you start to feel breathless, rather than open your mouth, slow down your pace. With consistent practice, you’ll be able to speed up.

Breathe lightly and slowly. This is a formal sit down / lie down practice. It involves taking in a little less air than you normally would do which should give you a feeling of ‘air hunger’. This feeling, whilst a little uncomfortable, should be tolerable. If it becomes stressful, take a few moments out and go back to it without overdoing the air hunger.

Once you’re making really good progress with the above (there’s no set length of time, it’s different for everyone), bring in diaphragmatic breathing. Initially, you may need to practise this independently of slow, light breathing but when you’re ready, you can start bringing them all together. How do you do this? Place your hands on the sides of your body just above your waist. By doing this, you should feel the gentle lateral expansion of your lower rib cage as you breathe in and then the contraction as you breathe out again. You will also feel your belly extend on the in-breath and contract on the out-breath.

The process of retraining one’s breathing can take time. It requires a gentle but consistent approach. It could be, for example, that a person with the Long Covid shortness of breath symptom will spend some time just getting used to nasal breathing. It can be the case that anyone experiencing chronic anxiety may need to proceed very gently with the slow, light breathing practice, consistently reducing it little by little over, perhaps, a number of weeks.

Consistency is key but equally important is to notice any changes, however subtle. The rewards can be very motivating. You may well sleep better, you’re likely to be a little more resilient and brain fog should reduce whilst energy levels show signs of improvement.

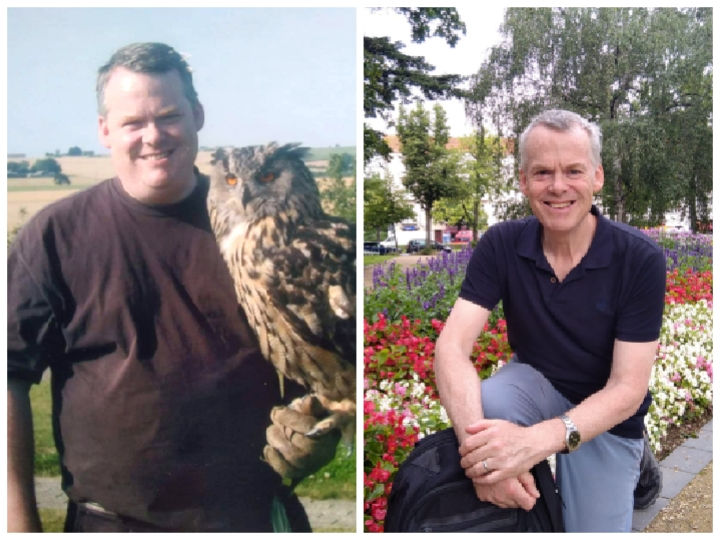

)_20230830_134131_0000.png)

Comments